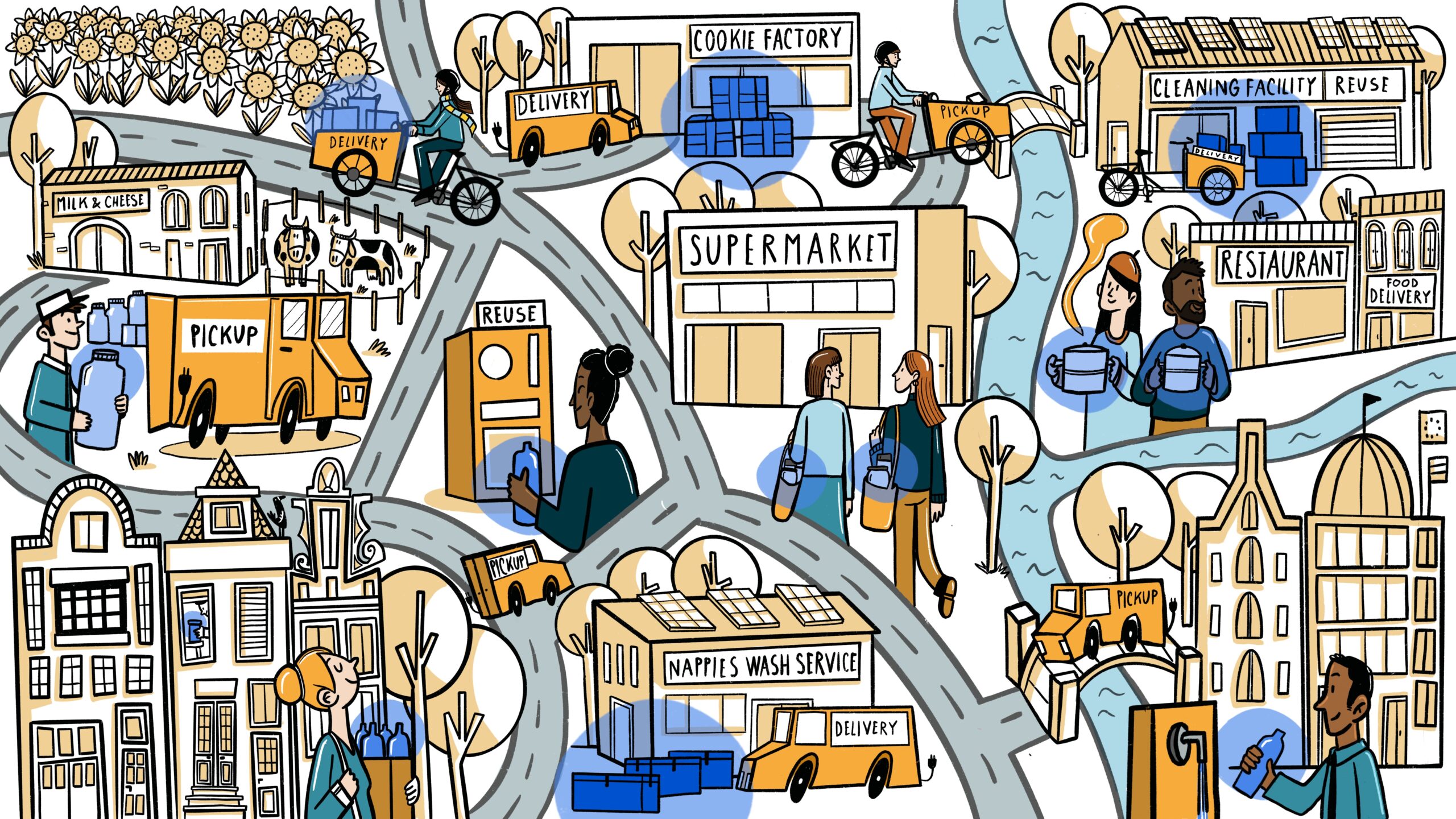

#WeChooseReuse campaign image. Iniative led by Break Free From Plastic members in Europe

As of March this year, central Berlin is seeing something new in grocery stores: Eight supermarkets will now allow people to return reusable takeaway cups they picked up from any of the 85 different participating local restaurants. Done via the existing Reverse Vending Machines (RVM) traditionally used for reusable beverages in Germany, this means eliminating the waste from takeaway coffees by using a modern system Germans are already used to. It has been common practice in the country to return empty bottles back to the grocery store for a small return deposit called “Pfand,” so that they can be reused multiple times. Now, the new reverse vending machines will allow them to do the same with reusable cups – and in the future with reusable foodware.

The pilot is part of the ReuSe Vanguard Project (RSVP), in which seven European cities are developing and testing reuse systems to prevent waste in the takeaway food and drinks sector. While it can sometimes fly under the radar, packaging from takeaway gastronomy is a massive pollution problem: in Barcelona, a recent audit found such packaging makes up 30% of public waste volume, and in Aarhus it’s a whopping 48%. Now, these cities are coming up with new partnerships to reimagine takeaway packaging in ways that fit into local cultures and practices, helping to develop solutions that can be reproduced elsewhere.

This comes at a particularly crucial time. In 2025, the EU’s Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR) entered into force, which is the first time there is a legal obligation for all EU countries not just to reduce waste drastically and increase genuine recycling but to center reuse. This is essential, because while recycling products and packaging at the end of the cycle is part of the plastic crisis answer, it’s really not enough on its own.

Transforming our systems requires new ways of thinking to ensure reuse fits into peoples’ lives, that solutions have a meaningful impact, and that companies can both be circular and profitable. The RSVP seeks to work together to find a way through these challenges. Most recently at the Reuse Economy Expo in Paris in May, representatives from the seven cities and a few new ones, civil society, businesses, policy-makers and other stakeholders came together to share what’s worked and what hasn’t.

One thing that became clear: location, location, location. The Berlin project contributes much of its success to placing the RVMs where people already go. In Rotterdam last year, a pilot tested the use of several RVMs strategically placed in the high traffic central train station, and demonstrated that a shared, safe and universal return infrastructure is technically and operationally possible. Yet to ensure better return rates over time, it was shown that this can only work with the right incentives in place, e.g. by making reuse, not single use, the default option for businesses and customers alike.

These lessons are helping direct the upcoming RSVP pilot in Paris. The French government has already put in place legislation that requires that 10% of the packaging placed on the market will have to be offered in reusable formats starting in 2027. Now, RSVP is designing the pilot to make this easier and more effective for Parisian customers and businesses, which will roll out next year – and location will be a key element. The Paris project will seek to place RVMs in both public and private places where people usually pass. This reflects the walking culture in the city to hopefully make it sufficiently accessible for both Parisians and visitors.

To build better reuse systems everywhere, the RSVP has updated its blueprint for takeaway food and drink projects to help local authorities and businesses effectively implement the EU regulation. It identifies five fundamental criteria for strong systems and shares learnings from existing pilots on how to achieve them. For example, systems must be interoperable, and the blueprint shows how projects in Berlin and Aarhus have ensured this. They have developed barcode cross-compatibility and clear background contrasts so they’re always readable and can be used across multiple systems by all stakeholders and machines involved.

The plastics crisis is multifaceted and widespread, and so must be its solutions – at every level, from national and international regulation to community-based projects. The EU has set a great example for other regions with the PPWR, but its goals can only be achieved through projects that work out what really makes a difference: from small but important logistical details like those mentioned above, to city-wide system design and level-playing field incentives for reuse. Testing and collaboration is the key to ensuring a workable and just transition toward a future free of single use plastics.

Published July 24th, 2025